Philadelphia Inquirer – October 10, 2016

We used to call it “presidents and wars.” Until the end of the 20th century, American history was generally presented in schools as a succession of conflicts with a focus on the leaders who guided us through them: Washington and the Revolution, Lincoln and Civil War, Wilson and the Great War, FDR and WW2.

Things became a little trickier after Vietnam and LBJ and Nixon. Faith in presidents, in America’s military. and in “the establishment” was shaken. Partly as a result of this shift, other sorts of history began to receive more attention.

All born in 1999 or 2000, they were toddlers on 9/11. Although the United States has been engaged in military conflicts in Afghanistan and the Middle East almost all of their lives, they do not view their country’s history primarily in terms of presidents and wars.

Twenty percent of the figures they listed were women. Most were abolitionists or women’s and civil rights activists, among them Susan B. Anthony, Rosa Parks, Alice Paul, and Harriet Tubman. Almost exactly the same fraction of the total were African Americans and most of that group were also seen by the students as civil rights activists, even if they were also scholars, athletes, or writers. They included W.E.B. DuBois, Langston Hughes, Jackie Robinson, and Malcolm X.

To these 21st-century teenagers, the most important history is social history. They would have trouble coming up with the names of Civil War battles other than Gettysburg, but they can easily recall several cities in which large-scale protests have followed the shooting of African American men by police in the past two years. And they are witnessing a presidential election campaign in which for the first time a major party ticket is led by a woman. When they think about American history they focus on the struggles of oppressed groups within our society to gain recognition and equal rights.

One of the first documents we read in September was the Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641), an early collection of rights and laws. The second of these liberties reads, “Every person within this jurisdiction, whether inhabitant or foreigner, shall enjoy the same justice and law, that is general for the [colony].” The students selected many figures who spent their lives fighting to make this principle of equality before the law a reality, and they see those battles still going on across the country.

Among their top three, Abraham Lincoln and Barack Obama tied for second. Obama’s prominence is a reminder that he was elected president when these students were in the third grade. He is the only president they have known. That he and the president who led the Union through the war that ended slavery appear beside each other is fitting. Obama recognized the tie himself when in 2009 he chose to take the oath of office on Lincoln’s bible.

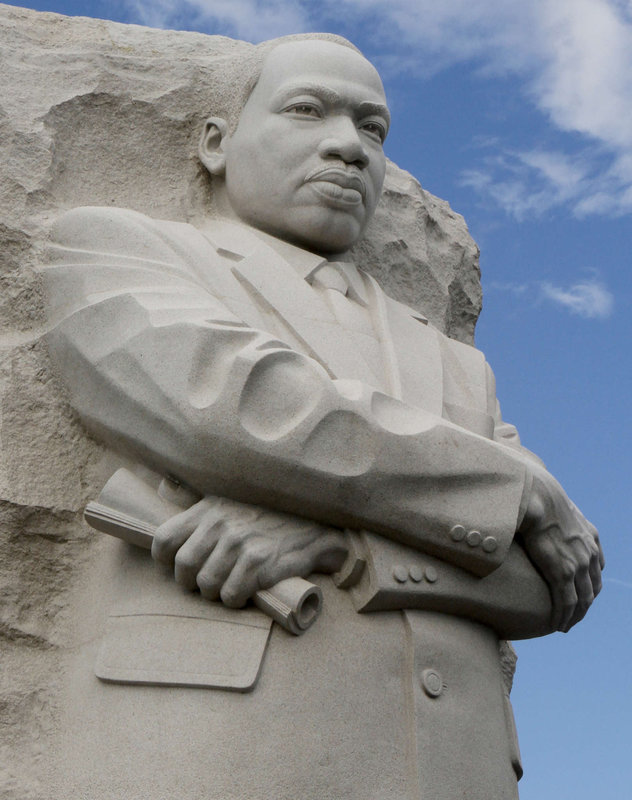

The clear first place went to Martin Luther King Jr. More than half of the students (most of them white) wrote his name and many assumed they did not need to say why.

In this deeply divided political and social climate, King’s words from his Letter from a Birmingham Jail could hardly be more relevant, “The question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice.”

Out of interest, did the Mass. Body of Liberties, whose language appears totally inclusive, actually apply to all living human beings in the colony, e.g. Indians? Were there any slaves in the colony or indentured bodies? Or sadly, was it like other documents in our early history that actually applied to limited numbers of human beings despite the soaring language? I’m always skeptical.

You are absolutely right about the Mass Body of Liberties. There are a number of striking contradictions in the language which are good fodder for class discussions. It talks about equality before the law, but there are later references to specific exemptions from certain punishments for “gentlemen,” for example, which make it clear that real equality before the law was, to say the least, an evolving concept. And still is.

I would hope my children get a better education in history than this.

Hmm. Do you mean that you’re not happy with the figures they chose (keeping in mind that they haven’t take the course yet)? Or are you a big fan of presidents and wars? I appreciate the feedback, but you’re not giving me much to work with.

It must be fascinating to be a history teacher and see the shift in what students are gravitating towards and how students are establishing their own understanding of history and who is important to them.

It is!

You piece lead to an interesting dinner conversation. My son would have added Rockefeller, but his other choices were more typical of the popular choices.

Rockefeller was mentioned by a student in one of my sections. Interesting Rockefeller anecdote – He provided the money that helped Spelman College (the most famous historically black college for women) transition from being a school to a college. The Spelmans were Rockfeller’s in-laws. They were also abolitionists and then supporters of education for the freedmen after the war, speaking of activists.

Does American history have to be about heroes? Social history, in particular, does not have to emulate the history of generals, presidents, and wars. Why not discuss, for instance, how near the end of the 19th century the Chinese reclaimed the swamp lands of California and made them the most productive farm land in the country? Why not discuss the New Woman in fin de siecle America? No need for specific names or heroes there (although some could be included). Just history from the bottom up.

You make an excellent point. Social history does not have to emulate the history of generals, presidents and wars. But people identify with individuals and some focus on extraordinary ones helps students connect with historical movements, trends and events of importance.

Do you also teach 1701 PA charter of privileges? Freedom from being ‘molested’ to support a state religion is there 70 years before Mass where they were still hanging religious dissidents.

We usually read the 1701 Charter. It’s a wonderful piece. This year we didn’t get to it because of time constraints. I would happily spend the whole year in the 18th century, if I could get away with it.

It is striking how much more oppressive and violent Mass Bay (the “city on the hill”) was than Philadelphia, at least for the end of the 17th and the first half of the 18th century. Credit the difference largely to the influence of Penn and the early Quakers.