Philadelphia Inquirer – March 29, 2013

Inquirer columnist Karen Heller wrote recently on the revival of interest in Thaddeus Stevens, the Pennsylvania congressman who led the Radical Republicans during and after the Civil War. “For a state with few legends among our elected politicians,” she noted, “Stevens is a giant.”

My students decided she was right. Other than Stevens, whose legendary status is well deserved, not many names from Pennsylvania’s political past come to mind. And we wondered why.

Pennsylvania played a pivotal role in early American history. In 1776, Philadelphia was the largest city in British North America. It was the headquarters of the Confederation for much of the War for Independence and became the second capital of the United States. Philadelphia was also a center, arguably the center, of trade, banking, law, and medicine.

The Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution were written in Philadelphia. Virtually all of the great American thinkers and leaders of the day walked its streets. Philadelphia attracted extraordinary talent from here and abroad – Ben Franklin from Boston, Thomas Paine from London, and Stephen Girard, the richest American of his generation, from France.

Why, especially in those early decades of the republic, did neither the city nor the state produce any presidents, major-party candidates for president, or even vice presidents? Philadelphia was full of well-educated, civic-minded citizens with the time and resources to serve.

Admittedly, the so-called Virginia dynasty (Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe) didn’t leave much room for other would-be chief executives, but Pennsylvania wasn’t even in the game. Massachusetts produced two early presidents, the Adamses, as well as Elbridge Gerry, a vice president. From New York came two major-party presidential candidates and two vice presidents. South Carolina also contributed two presidential candidates.

We did find a couple of Philadelphians who ran for national office in those days, among them Jared Ingersoll in 1812 and Richard Rush in 1820, but only for the vice presidency, and none was elected.

A few appear in the record among the advisers and secretaries of the early presidents, and the class decided this behind-the-scenes style fit the “Quaker city.”

The influence of William Penn and other members of the Religious Society of Friends helped make Philadelphia the most progressive and diverse community in the colonies. But Quakers also held some radical views for the times. They refused to support or participate in war and took an early stand against slavery, effectively removing themselves from direct involvement in presidential politics.

Philadelphians’ reputation for saying what’s on their minds may owe something to the Friends. Quakers have long been known for their commitment to speaking the truth, and though they have often been respected for this trait, it hasn’t always made them popular, or electable.

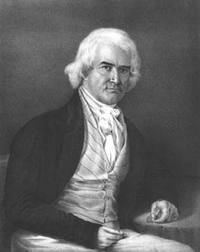

One local citizen, not a Quaker, did get within a heartbeat of the presidency. In 1845, George M. Dallas became the 11th vice president of the United States. No one in the class had ever heard of him. Ironically, he was a bitter political rival of James Buchanan, the only Pennsylvanian (from Lancaster) to become president. In her column, Heller described Buchanan as “arguably Pennsylvania’s worst elected official.” Dallas might well have agreed.

As the Philadelphian who came closest to the White House, and who also served as mayor of the city and as a U.S. senator, why not include George Dallas on the list of Pennsylvania political legends? There’s room.

As a new Pennsylvanian (2 years and 4 months) and a lover of your kind of history, you have me ordering books on Friends, Buchanan, and, most of all, George Dallas. I’m looking forward to learning more. Thanks.

George Dallas was an interesting character. He certainly served his city, state and country but with mixed feelings. He was only a Senator for 15 months. He became bored with being mayor. He accepted positions as a minister to Russia and England, but asked to be brought home from Russia. And there is no evidence I’ve seen that he lobbied for the VP spot on the ticket in 1844. Maybe all those things make him a good example of the Philadelphia style.

The theme of your article is one discussed with friends often since I left university.

It is a conundrum; those of us who are well educated, well traveled, with long professional experience decry the failures of many of those who get elected at all levels of government to even know what is good for society and to be able to solve problems more than their desire to stay in office.

We observe the inability of the big foundations to take that on, (William Penn makes efforts but is too polite), the timid attempts of very well meaning groups like the Committee of Seventy, an abhorrence of civic leadership needed from the big companies and the overwhelming drive for diversity and sensitivity instead of a drive for some brass knuckles civic leadership from the universities.

Thanks for you note. It’s great for the class see that others are out there are mulling over the same historical questions.

You make an important point about the role of foundations and universities and colleges which we will follow up on. They are very much a part of “the system” even as they attempt to push for reform.

I was briefly on Committee of Seventy and left upon realizing how many lawyers were on the board and how much each of the law firms depended on the income from bond work for the city. They were not going to rock the boat…and that is understandable.

Now the Committee is supported partly by the Wm Penn Foundation, but they are so long term motivated, so differential and so polite that they too are uncertain how forceful they want to be, even for the short and long term benefit of the city. That does mystify me.

All excellent civic questions/lessons for students.

Did your class discuss Digby Baltzell’s Puritan Boston & Quaker Philadelphia at all? It’s been MANY years since I read the book and took his class on social stratifications, but I found his insights really eye opening about the various paths the two cities took in terms of leadership. In retrospect, I’m not sure I agree with all his conclusions (need to re-read those books!), but a valuable perspective nonetheless.

I also read Baltzell’s book years ago. Can’t remember whether it came up in this particular conversation, but it has certainly influenced my thinking about Quaker Philadelphia.

There’s also a wonderful book called The Perennial Philadelphians that I liked a lot because it takes a very thoughtful and humorous look at our local culture.

I am the great, great, great nephew of George M. Dallas, the Vice-President.

One of the “monuments” to the Vice-President’s career is he fought very hard to get Texas admitted into the Union. For his efforts a small hamlet on the Trinity River was named after him. I wish they had given him a few hundred acres of it.

If you, or your students are interested in more on George M. Dallas (I) I suggest they look at “George Mifflin Dallas – Jacksonian Patrician” by John M. Belohlavek, The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1977. It is the most comprehensive biography of which I am aware.

I have the Vice Presidents 19th century lap top! It is a small wooden desk that fits on your lap which the VP used to write letters and such on the train trips between Washington and Philadelphia.

Thank you for the article and best wishes to your students and tell them the name still lives on.

George Mifflin Dallas (IV)

Thadeus Stevens was ,in my opinion ,not great . He led the prosecution trying to impeach Andrew Johnson for political reasons.

It took as Kennedy put it , a profile in courage ,Andrew Ross to defy Stevens and thus lose his status in the Senate to make sure that the President was not removed from office.

More outstanding : Still living – former Sen. Harris Wofford ,who co started peace corps and is at 86 still a worker for volunteerism . He just received the highest civilian medal on Feb 15, “presidential Citizen Medal”

Richardson Dilworth – reform Mayor of Phila in early 50’s

Gifford Pinchot – 1st chief of US Forest Service , who coined the term “Conservation” . He also was Gov of PA 1923-1927 and 1931-1935. His firing in the Pinchot-Ballinger case was a main cause why teddy came back and ran as a bull moose in 1912 ,opening the door to the 1st Southerner since the Civil War , Woodrow Wilson.

Good luck with your teaching . Hope this gives you some room for thought .

You’re right Thaddeus Stevens and the Radical Republicans were guilty of ignoring the Constitution in a number of ways. On the other hand, their failed attempt to help almost 4 million former slaves make the transition from having been the property of U.S. citizens to being U.S. citizens themselves was extraordinary, if also deeply flawed.

Good suggestions for other PA political legends.

I enjoyed the article and agree with you about George M. Dallas. I wrote and published an article on Dallas in the Weekly Press this past august, also published in Phactum for August-September.

excerpt from the article entitled – “A 19th century Mayor of Philadelphia elected Vice President of the United States”

“As I wandered about there, I eventually found a directory beside

one of the paths that helped me to locate the grave of the first Vice President born and raised in Philadelphia. It’s located on a nondescript corner on the right side of St. Peter’s building facing 2nd street at Lombard. Quite unassuming! He’s buried with several members of his family. His name is at the head of the

multiple names on the family plot. No adornments of any kind, almost like a Quaker grave.

Interestingly, the grave marker doesn’t even list him as a

Vice President of the U.S. Wow, how “Philadelphian” to keep such a secret! A Mayor of Philadelphia was elected Vice President of the country.”

Let’s not be too hard on Buchanan. He ordered, after all, the largest expeditionary force since the Revolution to take back Utah from the Mormons. Fortunately, Brigham Young, who had effectively become King of the Territory, was smart enough not to resist. But by the standards of the day, it was an expensive undertaking.

I have often read that Philadelphia was the second largest city in the English speaking-world at the time of the American revolution and never believed it.

I did a little research a few years ago and found that Bristol, England with 50,000 residents at the time was twice the size of Philly.

I would bet Dublin, Edinburgh and perhaps Liverpool were even larger in population.

You’re absolutely right. I also received a phone call from someone else who corrected the mistake. Thanks.