Philadelphia Inquirer – November 29, 2012

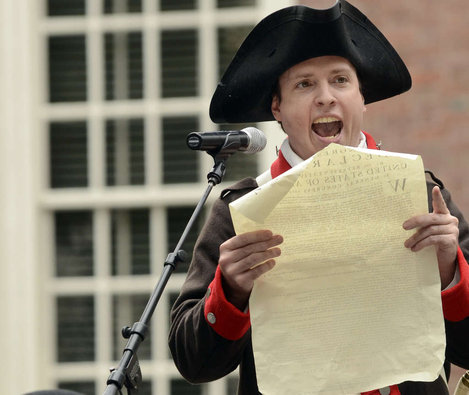

The first reading of the Declaration of Independence is reenacted behind Independence Hall in July.

Tom Gralish/Staff Photographer

In the aftermath of the election, several hundred thousand citizens have taken advantage of their First Amendment right to petition the government by expressing their desire to leave the Union on a White House website. The colonists of the 18th century, whose Declaration of Independence they invariably quote, had no such recognized right — much less a government-sponsored forum for their complaints.

Having spent the last month studying the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, my students have been intrigued by these recent displays of secessionist sentiment and the questions they raise. If we believe the people have a right “to alter or abolish” oppressive governments, as the declaration states, how do we know when that point has been reached? How oppressed do we have to be to justify rebellion or secession?

The answer to the latter question appears to be: Not very.

The colonists saw themselves as victims of a tyrannical ruler, King George III, but by all objective measures, they were among the least taxed, least oppressed, best fed, and most prosperous people on the planet. Almost a century later, when South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union, its white residents took that step to protect their social status and wealth, both of which rested largely upon the labor of 400,000 slaves.

We tend to assume that rebels rise from the ranks of the downtrodden. But quite often, those who actually manage to alter and abolish governments are insiders — members of local, if not national, ruling elites. It always helps to be connected.

In 1776, when the signers of the Declaration of Independence pledged “our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor,” they weren’t kidding. The declaration was not a petition; it was a statement by the colonies’ leaders that they no longer recognized the authority of the British Empire within their borders. By the time they made the break, the shooting had already begun, and the colonists had spent years organizing, protesting, petitioning, boycotting, vandalizing, and generally obstructing British efforts to administer the colonies.

The slogan “No taxation without representation” reflected the reality that Americans had no direct representation or official voice in England’s government. The same cannot be said of the South of the mid-19th century or of today’s would-be secessionists.

In 1860, a solid majority of South Carolina’s voters supported John C. Breckenridge, the Southern Democratic candidate who came in a distant second to Lincoln in the Electoral College, with 72 votes. This November (2012), the Democratic candidate won. Voters were free to back Breckenridge in 1860, just as they were to support Romney in 2012. But participating in an election and then deciding to leave the country when your candidate loses is problematic. It may be the only obvious restriction on the right to rebel.

Ironically, it was Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, who 25 years later noted wisely that “absolute acquiescence in the decisions of the majority” is “the vital principle of republics.” He added that “the minority possess their equal rights, which equal law must protect, and to violate would be oppression.”

It’s encouraging that today’s political leaders seem broadly committed to continuing the difficult and frustrating work of negotiation and compromise. None, as far as we could tell, has signed a secession petition.

It’s good to know that history scholars are still doing good work.

Thanks for putting secession in perspective.

Excellent. And extremely clear headed. Hope other feedback is similar to mine.

I am glad to see that you are engaging your students in civics and our nation’s history. I hope you are not indoctrinating them as so many of your teaching brethren are inclined to do.

I think you totally missed the point of the increasing interest in the subject of secession. It really has nothing to do with the fact that Obama was re-elected or that Romney was defeated. Lord knows that Romney was not the perfect candidate. It is the growing realization that the national government as intended by our Constitution at our nation’s founding has morphed into an unrecognizable and unsustainable entity that is clearly operating outside the boundaries of Constitutional authority or intent…..and it is never going back. It has become clear that as a result of mass communication, social media, improved organizing, educational indoctrination, media bias, and the creation of ever-increasing government dependency, certain political entities have succeeded in usurping the freedom of the citizens in the name of “fairness” or the “middle class” or the “common good”. It has also become clear to many that this will undoubtedly lead to tyranny by our national government.

I see what you mean. The government certainly exercises vastly more power than it did 200 years ago, or than the authors of the Constitution ever imagined it would. We do get the message through to our students that the more powers the government has the more limited are the rights of the people. I think you’re right that “going back”, in the sense of substantially shrinking the size of the government and its reach, is extremely difficult. Governments resist downsizing.

It is my opinion that young folks don’t get nearly enough of the message regarding the dangers of the increasing federal power.