Published in Independent Teacher, Volume 6, Issue 2 – May 2009

by Grant Calder

We have found that our history courses hold together better if there are a few clear centerpieces. These can be themes such as “revolutions,” the Industrial, the scientific, and the French, for example, or they can be documents such as the Constitution. We also keep alert for opportunities to tie the historical material to contemporary topics.

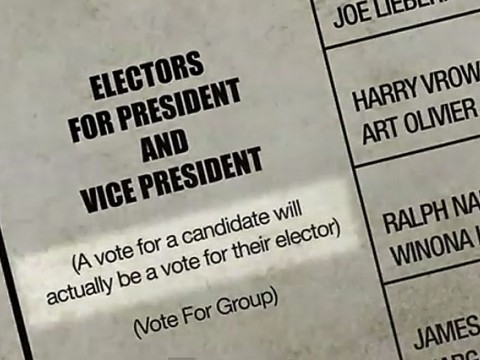

The juniors in our American History course were studying the Constitution last fall as the Presidential race reached its final stages. The constant references in the media to electoral votes and terms such as “swing state” focused attention on Article II, section 1, which describes the electoral system. This relatively neglected corner of the Constitution is scrutinized only rarely, as for example, when the electoral and popular vote results don’t match. This year’s class also happens to have grown up during the presidency of a man who was effectively appointed by the Supreme Court rather than the voters, so they were particularly interested in understanding how our Presidents are selected.

We used the Bush v. Gore case as our starting point and worked our way back through all of the Presidential elections, looking for evidence of other election irregularities. The students were given a list of the contests with the popular and electoral vote counts, the names of the candidates who earned 1% or more of the popular vote, their party affiliations, and the percentage of the eligible voters participating in each election. These sorts of data lists are superb teaching tools. They demand that the students flesh out the stories behind the numbers, and to some degree they can do this without even having to reach for other sources. They have the chance to discover the history for themselves. How could it be that Andrew Jackson won more popular and electoral votes than the other three candidates in1824 and lost the election? How could Samuel J. Tilden have won the popular vote in 1876 by a substantial margin and lost the electoral vote by one? What are the odds of that happening?

The single instance of a tie between Presidential candidates occurred in 1800 and produced the 12th Amendment, which left the system intact but prevented electoral vote ties. Given the fact that since then four Presidents have been chosen over opponents who had more popular votes, the students wanted to know why electoral voting has not been scrapped all together. They already knew from their Constitutional studies that United States Senators had originally been appointed by their state legislatures. Not until 1913 with the ratification of the 17th Amendment did they begin to be “elected by the people thereof.” The compelling argument was that the popular election of Senators made the system more democratic. Another century has passed, and the students felt that it was high time for a further democratizing alteration to the Constitution. Borrowing from the phrasing of the 17th, they drafted a new amendment which read simply,

Section 1: The President and Vice President of the United States of America shall be elected by the people thereof. Section 2: The Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

The second section was included so that Congress could work out the details of exactly how the party tickets would be represented on the ballots. Following the instructions in Article V, which describes the process for amending the Constitution, they sent their proposal off to their U.S. Congressmen, Senators, and state legislators. This part of the project gave us the opportunity to look at a number of websites maintained by our elected officials and compare the ways in which they communicate with their constituents.

When the persistence of certain systems or practices in our society does not seem to make sense, we always encourage our students to ask, who benefits? In order to answer this question with respect to the electoral system, we returned to the recent past, 1992, the year after many of the juniors were born. That November, 19% of those who cast votes, almost 10 million of them, did so for Ross Perot, but he did not receive one single electoral vote. Who benefited from the electoral system in that case? The students saw immediately that it was the majority parties, the Democrats and the Republicans. The state-by-state winner-take-all system of allotting electoral votes provides the dominant parties with a powerful mechanism for maintaining their political monopoly and suppressing third parties. I explained the argument that the electoral system acts as a form of check against certain vagaries of the mass popular vote. They didn’t buy it, but they did see that it makes certain citizens’ votes appear to count much more than others and that it limits the long term viability of so-called third parties. The current system is less democratic, less representative of the popular will, and less encouraging of political diversity than it could be. These students, who will be voting in 2012, also see the maintenance of the current system as a statement to them, to their fellow citizens, and to the world that Americans are not trusted to make this very important choice directly.

Some students who still read newspapers found that discussion of the drawbacks (and merits) of the electoral system was appearing in the media, as it always does, in the run up to a Presidential election. One brought in a column from the Philadelphia Inquirer whose author shared the view that Presidents should be elected by a popular vote but suggested that the individual states could simply change their instructions to their electors, requiring that they vote with the national popular majority and thereby obviate the need for a Constitutional Amendment. In fact, such bills are under consideration in many State legislatures. Whether they have any chance of passage is another question. In any case, the students were intrigued by the possibility of an alternative solution to the problem and very interested in poll data cited in the article, which showed that a majority of Americans has supported popular election of the President for the past fifty years. As a graded assignment, they all wrote letters to the editor expressing their appreciation for the article and what they had learned from it. They also pointed out what they thought was missing from the piece, an explanation of the advantages to the dominant parties (the Democrats and the Republicans) of keeping the electoral system. We submitted two of the best. Unfortunately, they weren’t printed. My guess is that we took too long to respond. After the students had read the column, discussed it in class, written their responses, and I had graded them, at least a week and a half had passed. Although the letters may still have been read by the Inquirer staff columnist who wrote the article, we will cut down the turnover time in future projects.

My interest in this whole exercise and my reason for writing about it grow out of a frustration I have always felt with the passive role of the student. Even if we manage to move away from lecturing and “get the students involved” in discussions and debates about the material we study, the sense remains that it has all been done before. Historical role-playing can be entertaining and a good way to learn about the past, but it does not bring students directly into the current political and social policy debates that are shaping our society. If we want them to be activist citizens, we should make every effort to show them how easy it is to participate in the debate, to express our views, and to interact with our elected officials and the media. The opinions of the general public matter. Individual citizens can have an impact on the political process. Tom Daschle, President Obama’s choice for Secretary of Health and Human Services, claimed that he decided to withdraw himself from consideration after reading a newspaper editorial. Students won’t always get that kind of response to their ideas, concerns, or protests, but that is a good lesson, too, and no reason not to keep on voicing them. As history teachers we can pay better attention to the opportunities available to connect the past with the present in our classes. We can train our students to use the skills they are developing and the knowledge they are acquiring from studying the past to weigh in on the issues of their own era.