Benjamin Franklin noted that.

A German of the time has other lessons for Pa. Today.

Philadelphia Inquirer – October 17th, 2009

In the mid-1700s a German named Gottlieb Mittelberger settled in Pennsylvania. After only a few years here, he returned to Germany and wrote a book about his experiences and impressions. By and large they were not happy ones and his intent was to discourage his fellow countrymen from emigrating to the colonies. “How wretchedly so many thousand German families have fared,” he wrote. Many “die miserably and are thrown into the water” during “the long and tedious journey” to the New World. Those who survive the crossing often endure “great poverty.” Families are often forced to “separate and are sold far away from each other,” as indentured servants, to pay the cost of their trip.

My students have recently read sections of Mittelberger’s book as part of their study of the colonial era. Ironically, many of the characteristics of Pennsylvania society he found deeply disturbing, they see as strengths. “Every one may carry on whatever business he will or can, and if any one could or would carry on ten trades, no one would have a right to prevent him” he wrote. “If a lad, as an apprentice, learns his trade in six months, he can pass for a master!” Mittelberger was also taken aback by the relative lack of social structures and the relatively higher status enjoyed by women. Either party may “repent an engagement,” he noted, and “it occurs oftener that a bride leaves her bridegroom together with the wedding guests in the church, which causes cruel laughter among said guests.” By Mittelberger’s fairly typical eighteenth-century European standards Pennsylvania was chaotic, unstructured and unregulated. But it was also freer. For a variety of reasons most immigrants stayed, and their legacy lives on in my students who, at least at this point in their lives, are generally willing to embrace the openness of American society.

Despite his misgivings, Mittelberger was clearly awed by certain elements of American colonial society. He wrote, “Liberty in Pennsylvania extends so far that every one is free from all molestation and taxation on his property, business, house and estates. On a hundred acres of land a tax of no more than an English shilling is paid annually.” In 2008 both presidential candidates claim that, if elected, they will somehow ease tax burdens for most Americans. This, despite the fact that Congress recently passed an amended version of the Bush administration’s $700 billion (or more) “bailout plan.” We still seem to equate liberty with freedom from taxes, but we also want protection from the natural boom and bust cycle.

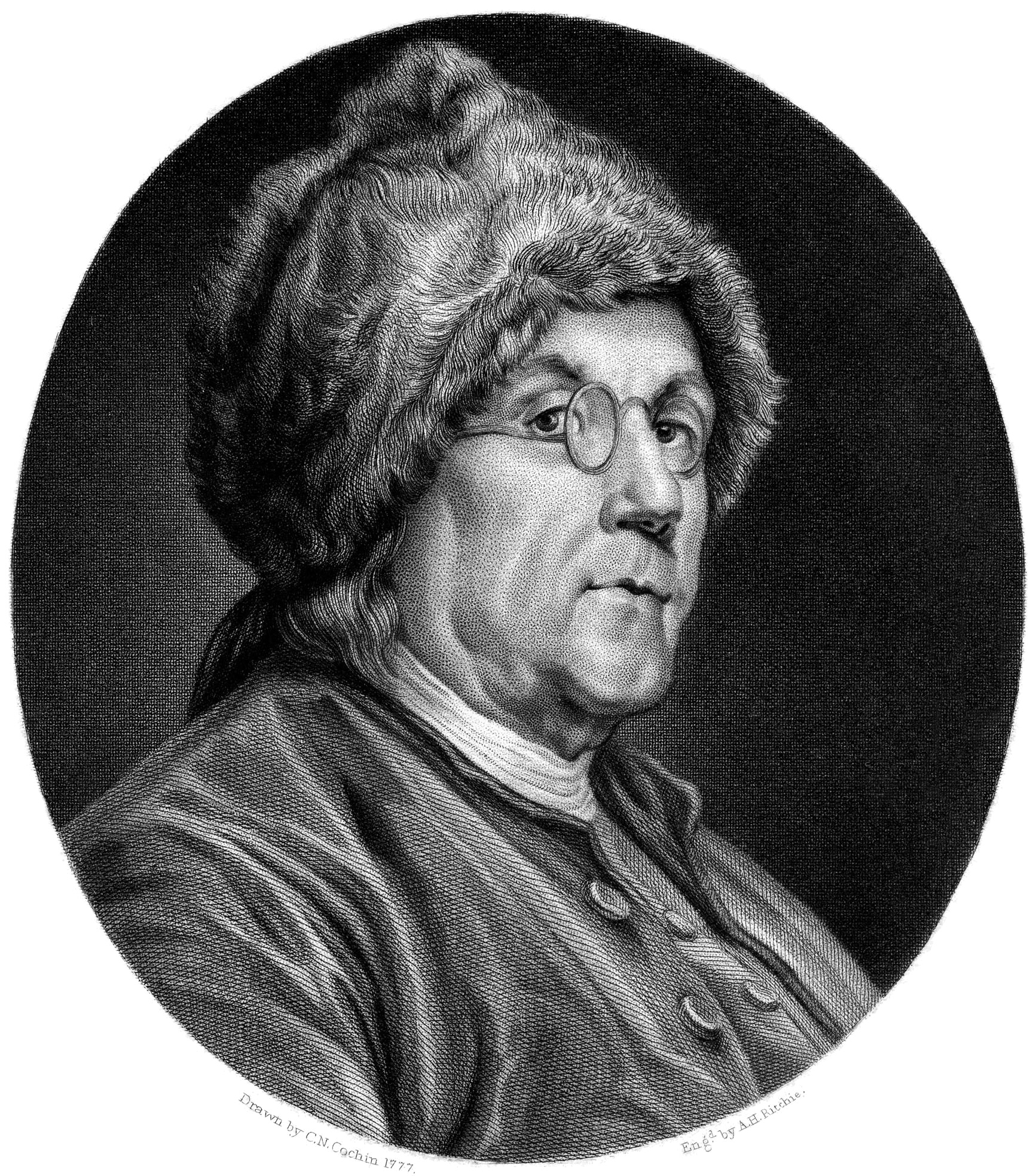

I believe my students see very clearly that as a country we continue to face exactly the same fundamental questions we did 260 years ago. How much structure is enough? How much is too much? What is our tolerance for chaos? And what are we willing to pay for the promise of economic stability? In comparison with those in Europe, our financial system has remained, even in the 21st century, relatively unregulated. Mittelberger’s reaction to the subprime crisis and current debate over “the bailout” would probably be a knowing shake of the head, but many of his contemporaries in Pennsylvania accepted the reality that with freedom comes risk. To paraphrase Benjamin Franklin, a great fan of American society and certainly a realist, people tend to believe they can give up some of their liberty in return for greater security, but they inevitably end up with less of both. This is a message perhaps we should heed as we enter this new phase in our history.