What can we learn from a flawed, ambitious legacy?

Philadelphia Inquirer – February 28, 2011

Do we need Black History Month? The debate waxes and wanes with the approach and passage of each February. There are serious arguments to be made against the 35-year-old tradition, but from my vantage point as a teacher, the practice of paying extra attention to African American history during this month still has its merits.

My students have already had many more opportunities than I did, a generation earlier, to become acquainted with such figures from black history as Benjamin Banneker, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman, as well as the likes of Philadelphia’s own James Forten and Octavius Catto. The evidence may be anecdotal, but it seems to me that Black History Month has played a significant role in bringing about this change.

Still, I think we could make better use of the opportunity to expose students to aspects of the subject that go beyond the pantheon of great African Americans. Individual stories are important, but much of black history is not biography. It’s also a record of events and trends, often involving complex and messy interactions among many blacks and whites. We should take time to highlight some of them, too.

One piece of that collective history that’s often overlooked began in February 1865, shortly before the Civil War ended, when Congress established “a bureau of refugees, freedmen and abandoned lands.”

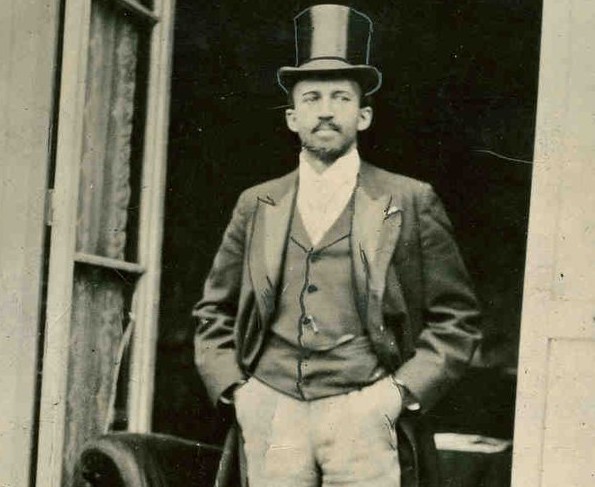

The great African American scholar and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois described the “herculean task” delegated to this agency as nothing less than “the social uplifting of four million slaves to an assured and self-sustaining place in the body politic.”

With its expansion in 1866, the institution became the de facto government of the entire unreconstructed South. Nothing like it had ever existed anywhere.

The Freedmen’s Bureau survived for only four years, but during that time the range of its functions far exceeded that of the federal government itself. The bureau exercised legislative, executive, and judicial powers. It made laws and enforced them, set and collected taxes, kept records, helped establish the institution of marriage among the freed slaves, and assisted in the writing of contracts between black employees and white employers.

In the bureau’s courts of law, freedmen could sue whites — and win. The bureau ran hospitals, distributed food, and paid pensions to many of the black Southerners who had served in the Union army. And it established schools.

At the end of a recent unit on the Freedmen’s Bureau, my students agreed that the nation had a responsibility to help the former slaves. They also concurred with Du Bois’ qualified judgment about the bureau — that, “even with imperfect agents and questionable methods, the work accomplished was not undeserving of commendation.”

At the same time, the majority of the class concluded that the bureau’s reach far exceeded the limits of legitimate constitutional authority. There was no separation of powers; there were no checks and balances. And even if that could be justified in wartime, almost all the bureau’s work was done after the Confederacy’s surrender had been signed.

The Freedmen’s Bureau was part affirmative-action program and part nation-building experiment, and it remains, arguably, the most radical attempt at social engineering that Americans have ever undertaken. Its modest successes, and perhaps its greater failures, give us much to consider.

As a society, what do we do when we know a cause is just but that constitutional principles are being compromised? And how far should we go to protect the minority from the majority?

At the turn of the last century, Du Bois wrote of the Freedmen’s Bureau: “To-day, when new and vaster problems are destined to strain every fibre of the national mind and soul, would it not be well to count this legacy honestly and carefully?” That’s still good advice.

Sir,

Your column in today’s Philadelphia Inquirer was fascinating. Though a college graduate, with a liberal arts focus, I confess that I had only barely ever heard of the Freedom Bureau. Given its importance in our history, and relevance to issues of today, it could be the focus of an entire course in middle school or higher. I have one burning question, if you will. In the region under its control, did the Freedom Bureau actually replace any or all of the three existing branches of State and/or Federal government, or were their some type of dual(ing) institutions?

Of course, the age-old moral question of whether the end can justify the means is just as relevant today. Did the legislators who fled Wisconsin and Indiana demonstrate moral courage, or disrespect for our democratic process? In our highly partisan world, nearly all democrats would say “A”, and nearly all Republicans would say “B”– plain and simple. Yet to an independent voter, like myself, it raises complex questions where the lines can become blurry. How do you balance the fact that elections must have consequences — or democracy is a sham — with the legitimate rights of the minority?

Your students are very fortunate.

Jim Lundberg

Newtown, PA

Great question about the Freedmen’s Bureau’s powers – Yes, the Freedmen’s Bureau initially acted in place of the southern state governments, which ceased to exist for a period, and it was also the arm (quite an independent one) of the federal government in the South.

I couldn’t agree with you more that the story of its activities (successes and failures) could easily justify a year long course.

Sadly, even in colleges it’s extremely rare to find a single semester course on the Freedmen’s Bureau.

No.

We don’t need any kind of month. I’ll bet 99% of the people in the USA don’t know what “month” it is nor do they care/celebrate/commemorate/or pay a bit of attention to the topic, whatever it is. We also don’t need Boss’s Day, Secretary’s Day, or any other Whatever Day’s. I tell my kids to be nice to me once in a while all year long – not just on one Sunday in May. It’s ridiculous – simply Hallmark’s and the flower companies’ way of making money!

Study Black History, Asian History, Ancient History, Hispanic History, German History, any other race/nation’s history all the time – any time – but don’t have one month dedicated to one race. Isn’t that being “racist”??

To answer your last question first – No. Setting aside some time to recognize the individual achievements and collective history of a persecuted minority, first enslaved and later marginalized for generations by the white majority, is not racist.

I doubt Hallmark makes any money from Black History Month.

You’re right that many Americans may not even be aware of February’s status as Black History Month, but if that’s so, then it’s clearly not much of an imposition to have so designated.

And for those who take advantage of the opportunities made available during February to expand their knowledge and appreciation of black culture and history, good for them.

Some of the institutions and practices such as black colleges and black beauty pageants originated in times during which blacks were denied entrance to white colleges or white beauty pageants. Their separateness was forced on them.

Do we still need them, now that there are fewer racial barriers? Not up to me to decide, I have only had the experience of being part of the white majority.

Where did YOU study history. Blk history month which started out as Negro History Week (2nd week in Feb) began in 1926.

So what if it was expanded to a month in 1976. You watered down your excellent point with that one misleading sentence at the beginning of your article.

Thank you for your note.

I do know about Negro History Week.

I didn’t think it watered down my point not to mention it because the current debate revolves around whether we should (continue to) have an annual Black History Month by Presidential declaration.

I found it interesting that Carter Woodson apparently chose the 2nd week in Feb, because he believed it to be the week of both Lincoln’s and Frederick Douglass’ birthdays. As far as I can tell Douglass himself didn’t know his birthday. His gravestone lists two possible birth years and no birthday.

Very timely article on something most Americans know little or nothing about. In my radical declining years, I wish the Bureau had had another eight years to get some new practices settled in such a way that Jim Crow could have been avoided. Granted it was an authoritarian regime in a time when the South was basically conquered territory, but what was to be done? Ultimately, Congress failed to attach requirements to states’ reentering the union that could have at least tempered the reimposition of “slavery”. But the northern states and the presidency and supreme court also failed by not enforcing the post-war amendments for another 100 years, all in all a horrible story of profound racism.