The document’s admirers must contend with slavery

Philadelphia Inquirer – Jan. 13, 2011

Congress’ reading of the Constitution last week seemed like a fairly benign way to pander to the majority’s tea-party base. It wasn’t supposed to involve any debate. But House Democrats, adapting quickly to their new minority role, managed to find a way to take issue with the event.

It turned out that the Republican leadership had chosen to omit the Constitution’s references to slavery. Claiming “whitewashing,” some Democrats were able to score points in this bizarre channeling-the-ancestors contest, which has become a popular pursuit among Washington politicians and Supreme Court justices.

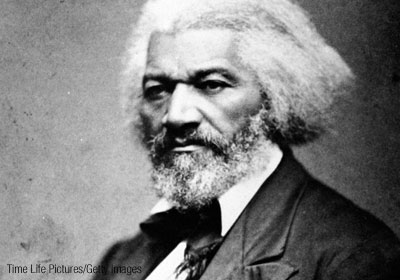

One ancestor worth consulting on this occasion and topic is Frederick Douglass. Born a slave, Douglass became our greatest spokesman for abolition. His autobiography occupies a well-deserved place on many high school reading lists, but his speeches get less attention than they deserve. This Congress should read one that my students recently studied, titled “The Constitution of the United States: Is it Pro-Slavery or Anti-Slavery?” It was delivered a little more than a century and a half ago, a year before the Civil War began.

By 1860, Southerners were well-practiced in citing various passages of the Constitution to support their right to maintain and expand the institution of slavery. These are the very passages whose deletion – on the grounds that they have since been amended out of the document – drew criticism from the Democratic side of the aisle last week.

In his speech, Douglass addressed every part of the Constitution that Southerners had cited to justify slavery. In addition to attacking each reference individually, he pointed out that the words slave and slavery appear nowhere in the text. He said, “I demand that the law that completes such a purpose” – that is, turning people into property – “shall be expressed with irresistible clearness. The thing must not be left to inference, but must be done in plain English.”

Douglass put the defenders of slavery in the position of having to admit that the Constitution was written in code, which in some respects was true. The three-fifths clause and the fugitive-slave provision, for example, both referred to slaves as “persons.”

Douglass would have none of it. As he put it, “the paper itself … with its own plainly written purposes, is the Constitution.” Its meaning was in the text, he insisted, “not the secret motives or unexpressed intentions of any body.”

Douglass focused on the broad ideals embodied in the Constitution. The preamble begins “We the people,” he noted, “not we the white people, not even we the citizens, not we the privileged class, not we the high, not we the low … but we the people, we the human inhabitants. …”

He declared that “the constitutionality of slavery can be made out only by disregarding the plain and commonsense reading of the Constitution itself; … by claiming that the Constitution does not mean what it says, and says what it does not mean. …”

This was not just an example of fancy footwork in the battle of words that foreshadowed the battle of arms. Douglass was exhorting Americans not to ignore our history, but to assume ownership of our Constitution and our government in our own times.

There is no point in arguing about what the founders intended, he said: “These men are already gone from us. … They were for a generation, but the Constitution is for the ages.”

Douglass lived to see slavery abolished by the 13th Amendment. He also lived to see it succeeded by segregation. But he never lost faith in the ideals for which we continue to strive – the ones contained in what he called the “fair-seeming and virtuous language” of the Constitution.

Very much enjoy reading your pieces in the Inquirer. Your students are lucky to be introduced to the primary documents that bring history to life down to every detail and to have the opportunity to hash it apart and think critically and creatively about it (especially in this day and age of rampant political blathering!!).

Jenny

Great Article in the Inquirer! But, you just can’t let it go;can you? “Congress was pandering to the majority’s Tea Party base”………………………..the most dishonorable thought in your entire beautifully polished article. I can see you are a another master teacher of history that has fallen prey to the progressive/liberal persuasions and are passing these persausions on to the young minds in front of you everyday; shame on you! I hope these young minds coming from historically conservative families have a chance and dare to confront your progressive/liberal influences in the classrom without retribution! John Haag Moorestown NJ 609-8208436 ( A school administrtor for over forty years that has observed progressive/liberal teachers twisting young minds)

John –

Many thanks for the note.

I thought I was fairly balanced in this one.

I gave the Republicans (really John Boehner) a little poke, because the tea party did push him to do the reading of the Const. Not that I have a problem with reading the Constitution. I carry a pocket copy with me all the time.

But the Democrats were playing politics just as much by making an issue out of which “version” would be read. Their getting worked up about the “references to slavery” being left out seemed as nonsensical as getting upset that the original presidential electoral system segments in Article II, superseded by the 12th amendment, weren’t being read.

I kind of like the tea party, I tend to be a strict constructionist too, as was Douglass.

Best regards,

Grant

Thank you for your fine discussion of Douglass and the issue of slavery in the early republic. Though I have not read the Douglass essay you mention, I think you make a good case. Douglass is certainly worth reading, as you emphasize. (We included “What, to the Slave is the Fourth of July,” in our American Ethics, 2000.) What seems certain to me is that we cannot ignore the issue of slavery in the early republic–whatever else we have to say about it. Douglass was right to make the defenders of slavery point to the coded character of the issue in the constitution of 1789, but there were evident difficulties in that approach–including the Dred Scott Decision, of course, which had virtually eliminated the possibility of further “great compromises.” The Supreme Court (dominated by Southerners) had made it official that slaves were property under the law of the land, throughout the U.S., and there was no legal way to free any southern slaves merely by abolitionist northern state laws.

I think we need to keep in mind, too, that slavery is an instance of exploitation or labor, and though we got rid of official chattel slavery by means of a great Civil War, we didn’t get rid of the tendency to exploit and exclude for personal benefit and profit. You point this out in a way, regarding the post-Civil War developments, and one may certainly consider the Gilded Age as a whole–both North and South.

You may find the following book of interest on related topics–my edition of Emerson’s essays, The Conduct of Life, published by just before the outbreak of the Civil War:

http://www.amazon.com/Conduct-Life-Ralph-Waldo-Emerson/dp/0761834117

The ending of my Introduction to the volume is of particular interest. It presents Emerson’s analysis of what went wrong at the time of the constitutional convention–in the context of Emerson’s discussion of freedom and fate. Of course, it remains true that the founders of 1789 went to some considerable lengths to keep any mention of slavery out of the document–and they hoped that it would disappear. But, they failed to act, and Emerson points to opportunity and motives–as any good lawyer would. “Great crimes,” he wrote (or words to this effect) “bring great punishments.” He had no doubts on what was about to happen to us as he published Conduct, in late 1860–after Lincoln’s election as President.

I’ve attached a copy of the Introduction. I hope you will find some useful intellectual ammunition.

I hate to say it, but I agree with the Republicans on this one. The purpose in reading the Constitution isn’t a history lesson, it’s to remind legislators of the limits placed on their authority. They have to be consistent, though (omitting the Prohibition amendment because it was later repealed).

— Ben9

Here we go again, another column about one the saddest parts of our American history.

For a change I would like to hear from the American Indian culture, the Eskimo’s, the native Hawaiians, ancestor’s from the Spanish-American war.

I’m sure they also have very painful stories that need exposure for their own healing to take place.

— truth B told

I thought Douglass’ speech highlighted a positive aspect of that era – that there were extraordinary African Americans who played vital roles as abolitionists, as writers, as teachers, as soldiers in fighting to end slavery and to help heal the wounds of three hundred years of oppression.

Of course, you’re right, there are many other tragic stories to tell.